As part of the rolling world premiere of Malcolm X and Redd Foxx Washing Dishes at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem, this review comes from the production’s recent run at City Theatre in Pittsburgh. The production will continue its journey to Virginia Stage Company later in the premiere cycle.

Opening nights tend to be pleasant occasions, with warm audiences often made up of members of the creative team, family, and seasoned theatergoers. I have the impression that opening-night audiences are generally more inclined to enjoy a show, for a variety of reasons. Still, the experience is, of course, far more powerful when the show is genuinely good, as was the case Friday night at the opening of Malcolm X and Redd Foxx Washing Dishes at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem, at City Theatre.

I sensed a quiet, delicate complicity among those present, a shared feeling of, “That was really good; how wonderful that we were all here together tonight.” And indeed, it was.

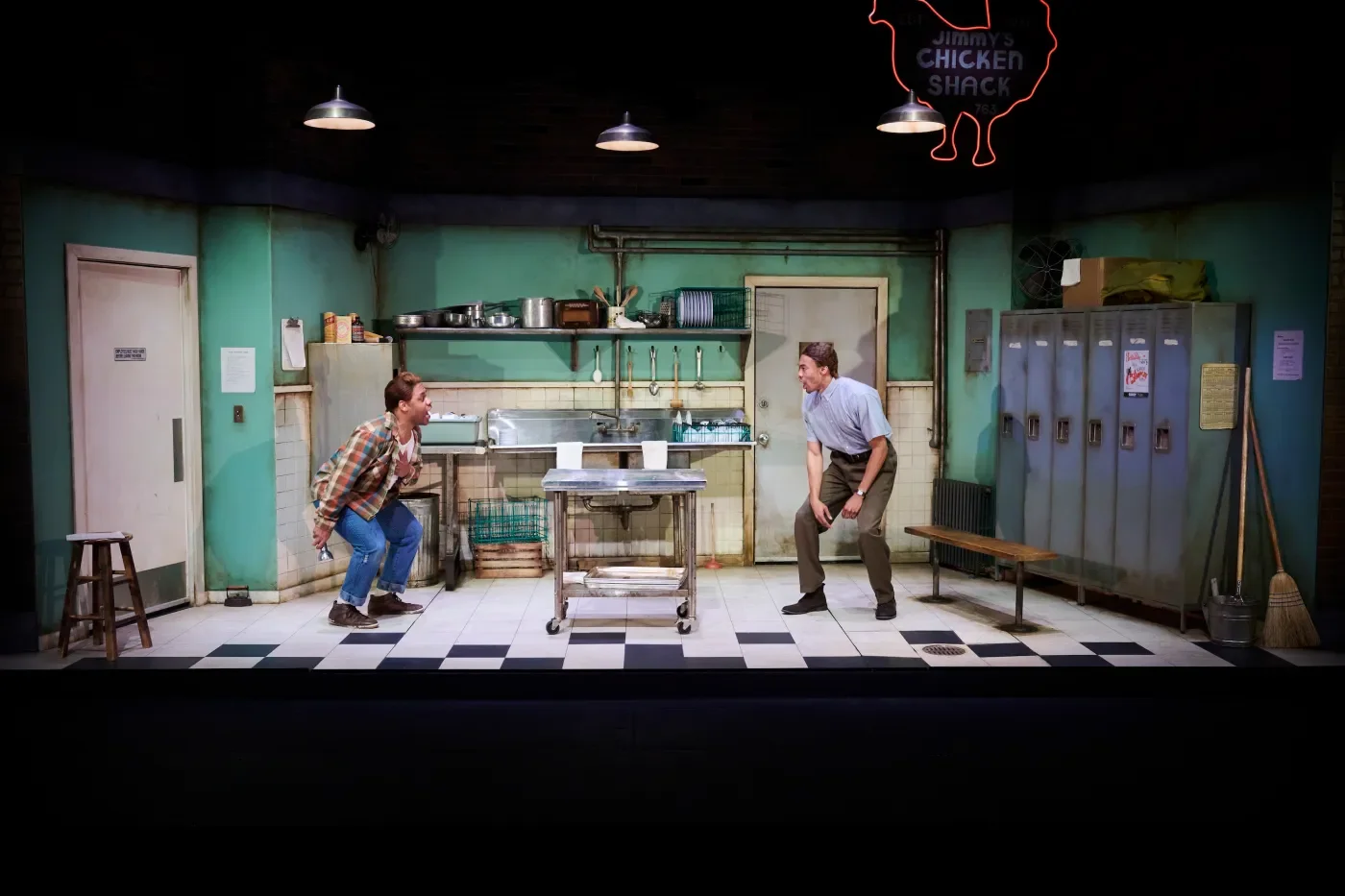

Malcolm X and Redd Foxx Washing Dishes at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem (Image by Kristi Jan Hoover for City Theatre)

Malcolm X and Redd Foxx Washing the Dishes at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem — I repeat the title here because it really is that good — by Jonathan Norton had its co–world premiere on a freezing Pittsburgh night. Inside the theater, however, the temperature was decidedly different. The warmth generated there was the result of a collective effort by City Theatre in partnership with Dallas Theater Center, TheatreSquared, and Virginia Stage Company. Well, it sometimes takes a village to make theater.

The play’s narrative unfolds within a fertile creative universe located in the interstices between history — what is documented, archived, and more or less agreed upon as having happened in the past (always a partial memory) — and story: fiction, invention, and creative fabulation on the part of the artist. Norton began his work from a small particle of history.

While reading a biography of human rights activist Malcolm X, he learned that before his crucial political engagement, Malcolm had worked for a time as a dishwasher at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem, New York, alongside comedian Redd Foxx (before his career as an actor and comedian took off, and long before the massive success of the sitcom Sanford and Son). From this historical nugget, interwoven with other rigorously researched information, Norton crafted a fictional narrative that is not only funny but also deeply moving, one that can be appreciated even by spectators who know little or nothing about these two historical figures. I count myself among them.

While I was familiar with Malcolm X’s political work, I had never heard of Redd Foxx prior to seeing the play. This, however, did not come close to being an obstacle to my experience as a spectator. Norton’s brilliance lies in having written a tightly woven narrative in which all necessary elements are present and seamlessly integrated. Of course, the horizon of expectations and the degree of connection between History and fiction will vary widely among audience members, depending on their prior knowledge of these figures—but this is never a problem, only a nuance of reception.

Dexter J. Singleton’s direction is confident and precise in what it sets out to accomplish. The language and look are realistic and closely aligned with sitcom aesthetics —the scenic design (Kimberly Powers) and costume design (Claudia Brownlee) are crucial to this endeavor and deliver impeccable characterization. All the stage action unfolds in a single space, meticulously rendered: the backroom of a Harlem restaurant in the 1940s. Two doors — one leading to the alley and the other toward the kitchen and dining room — enable brisk entrances and exits, while also metonymically establishing the connection between this space and two other spheres that function as driving forces of the dramaturgy: the rest of the restaurant and the world outside, the sociopolitical environment of Harlem (and the United States more broadly) during the still-segregated and turbulent 1940s.

The scenes unfold as we witness the relationship between the two characters develop within this space that is not only one of labor, but also of affection and friendship. We see two young Black men, their aspirations and their struggles. Here, Norton’s fabulation comes into play by imagining the possibility that this encounter between the two figures may have been, perhaps, formative for their trajectories —for who they would later become: two individuals who would each, in their own way, leave a mark on the country’s history. The narrative weaves together the characters’ personal concerns with two directly connected driving forces: labor and sociopolitical struggle. This is handled masterfully, both in the text and in the staging. The door leading to the rest of the restaurant (kitchen and dining room alike) represents the structural hardships faced by the vast majority of Black Americans at the time — precarious working conditions and low-wage jobs. The door that opens onto the alley, in turn, symbolizes the characters’ connection to the sociopolitical sphere: from outside we hear police sirens repressing Black political mobilization, which in the 1940s took the form of significant riots, such as those in Detroit and New York, both present as a backdrop to the dramaturgy.

One particularly important element of the production that deserves close attention is the soundscape. Kudos to Howard Patterson’s sound design. Although the show centers on the relationship between the two characters, it is through sound that many of the conflicts enter the stage. When the dining room door opens, we hear the pleasant music enjoyed by the restaurant’s customers (a sonic marker of class conflict and workplace inequality). And from the radio strategically positioned above the sink where the dishes are washed, we hear not only period music but, crucially, radio news broadcasts, as an essential narrative device that stitches together what we see onstage with what remains offstage: riots, police repression, violence, and the Black community’s uprising against centuries of oppression and inequality.

Through the micro-sphere of these two young men’s lives, the show beautifully captures the complexity highlighted by the Double V Campaign during World War II: Victory Abroad and Victory at Home. Launched in 1942 by the prominent African-American newspaper The Pittsburgh Courier, the campaign brought into focus the central contradiction of the war for Black Americans: how to fight for democracy abroad while living under segregation, racial violence, and economic exclusion at home. The development of the fable and the way the characters’ conflicts are shaped by historical forces also echo a key thesis of Malcolm X, who conceptualized the Black condition in the United States as a form of “internal colonialism,” arguing that Black urban communities functioned as occupied territories subjected to economic extraction, political domination, cultural erasure, and police violence — conditions analogous to those of colonized nations abroad.

All of this is present in the production, but never in a didactic, pamphleteering, or overly explanatory manner. Quite the opposite. At its core, the story is about two characters and the development of their friendship, which is precisely what makes the narrative so universal. Still, the external forces tied to the historical and political moment directly and indirectly affect the characters, and they are introduced with great skill by Norton’s text and translated to the stage with remarkable precision.

Edwin Green and Trey Smith-Mills (Image by Kristi Jan Hoover for City Theatre)

Edwin Green (“Little” / Malcolm X) and Trey Smith-Mills (“Foxy” / Redd Foxx) embody their characters with precision and charisma. They engage the comedic language with sharpness and ease, yet without resorting to formulaic shortcuts, allowing the play to move beyond sitcom conventions when deeper complexity is required. Their chemistry and quality of play clearly stem from generosity, mutual respect, and a great deal of technique and rehearsal.

Malcolm X and Redd Foxx Washing Dishes at Jimmy’s Shack in Harlem allows us to engage with history without it becoming a historical drama. It invites critical reflection on the United States’ past amid abundant laughter. And, above all, it entertains us deeply, while also prompting reflection on the present, without erasure or forgetting. History does not remain in the past; it is made in the present and projected into the future. Let us not forget: The past always comes back to collect.